1975-1985

For context and contrast, he was just as tall as McNamara without the glasses yet with trench coat and slick-back hair. We did not go deep-sea fishing for father-son outing. He only spent Sunday mornings with me. Our routine. His afternoons were for the other, his second wife and child.

So I grew up, with abnormality as norms. Watching my Dad go about his work, his music and lust for life. Relatives and colleagues adored him in a warring society (he was a French-army discharge).

Floated South at the time Vietnam partitioned, he cared for his mom (my roommate) and grew to be de-facto patriarch given his older brother already deceased, and younger, martyred.

My brother took up after my Dad much more than I. They spent time in Northern Vietnam, before my time, then Northern Virginia, in Dad’s last two decades. But that is ahead of this story.

For background of unfortunate incidents in my refugee alley, you would have to read “Outlive the Bully” ( search other blog). Perhaps seeing me abandoned most of the time, neighborhood-watcher, an older pharmacy student took me out for a game of ping-pong or a game of pool. No deep-sea fishing there.

I would catch any ride with older male neighbors served as surrogates for my Dad ( most residents were laborers who toiled for foods. Of late, I passed by that old neighborhood and found no kids’ playing, only iron-bars and enclosed fences).

When the spaghetti hit the fan on Vietnam last days, we went through reverse-abandonment i.e. leaving our Dad behind. That pattern of chronic abandonment (betrayal) eats me up and still is in the bones.

So much so that on a lonely weekend night, at a fast-food joint, Campus Crusaders approached me, thinking I was an easy target. OK, tell me more about the Prodigal Son. God abandoned his Son just like I abandoned my father?. My brother, a Medic, was more conscientious and better-suited for the dedicated brother role. He sponsored my Dad over after that decade of absence and silence.

Since I did not know how to handle sudden separation, I ran around campus like that native American who “flew the cuckoo’s nest” with Juicy Fruits at the ready: from Mt Poconos as a camp counselor to Wilkes-Barre as an intern at the station (ABC-TV56).

In total denial I got busy with Penn State Choir, the Group Singer (nursing home free weekly concert), those Northern Baptist Sunday potluck meals (luckily, it wasn’t cult-like) as substitute for family meals. I revered father figures: Raymond Brown, choir conductor, Paterno, football coach.

I even cried my heart out at a friend’s father’s funeral to the surprise of my other friend. She has thus far become a therapist (but lack of training at the time of post Watergate, post Vietnam era on a lily-white campus).

People like the McNamara or the Lodges did not comprehend people like me (two times a refugee of French and American war). We were twice dis-lodged (no pun intended), hence, cosmetically picked up surface nuances (fourchette, brilliantine – pronouncing with a thick accent without neglecting our native tongue – itself with a Northern accent, sufficiently qualified for locals’ discrimination of sort. I was a bit ostracized when growing up in the Southern alley of Saigon.

Besides finding fatherly substitutes (unconsciously) I went about volunteering at multiple refugee camps in Asia – this was not sure out of guilt or compassion, but for sure to make amends, since I hate to see abandonment (for the past decade, I have lived up to this compulsive obsession by raising a child not of my own).

When my Dad finally arrived in Northern Virginia, I flew back from the West Coast to see him. His hollow cheeks told me there hadn’t been adequate dental care or nutrition even. I also noticed rare laughter – plenty at our extended family gathering in earlier decades.

He often showed me his other daughter’s letters from home. He commented often on how the luxury rental run so smoothly as we drove around the beltway. Fall foliage in N VA was quite a site: leaves lingering on on the ground until early Winter, the sight when he passed away in a Winchester home. My nephew and I cleared out his double-up dorm-like room and gave away meager stuff in his closet. No more apple sauce and shoe shine for the man of Chateaubriand and cafe au lait.

I once saw him tearing up at the mention of his other woman. “How? it’s so far away!”. In my Mom’s case, it had been a matchmade marriage, perhaps out of duties more than love.

I don’t know the answers to a man’s heart, even when it’s my Dad’s. I certainly did not know what and whom he had seen for a decade. I just knew I tried very hard to make it on my own, without guidance and without the benefits of his experience. People perhaps saw in me that paternal void, just as back then when my mom by default played “single” mom and me half of the time with dad-size hole, like the Krispy Kreme glaze donut holes he and I shared at Bailey Crossroads back in 86.

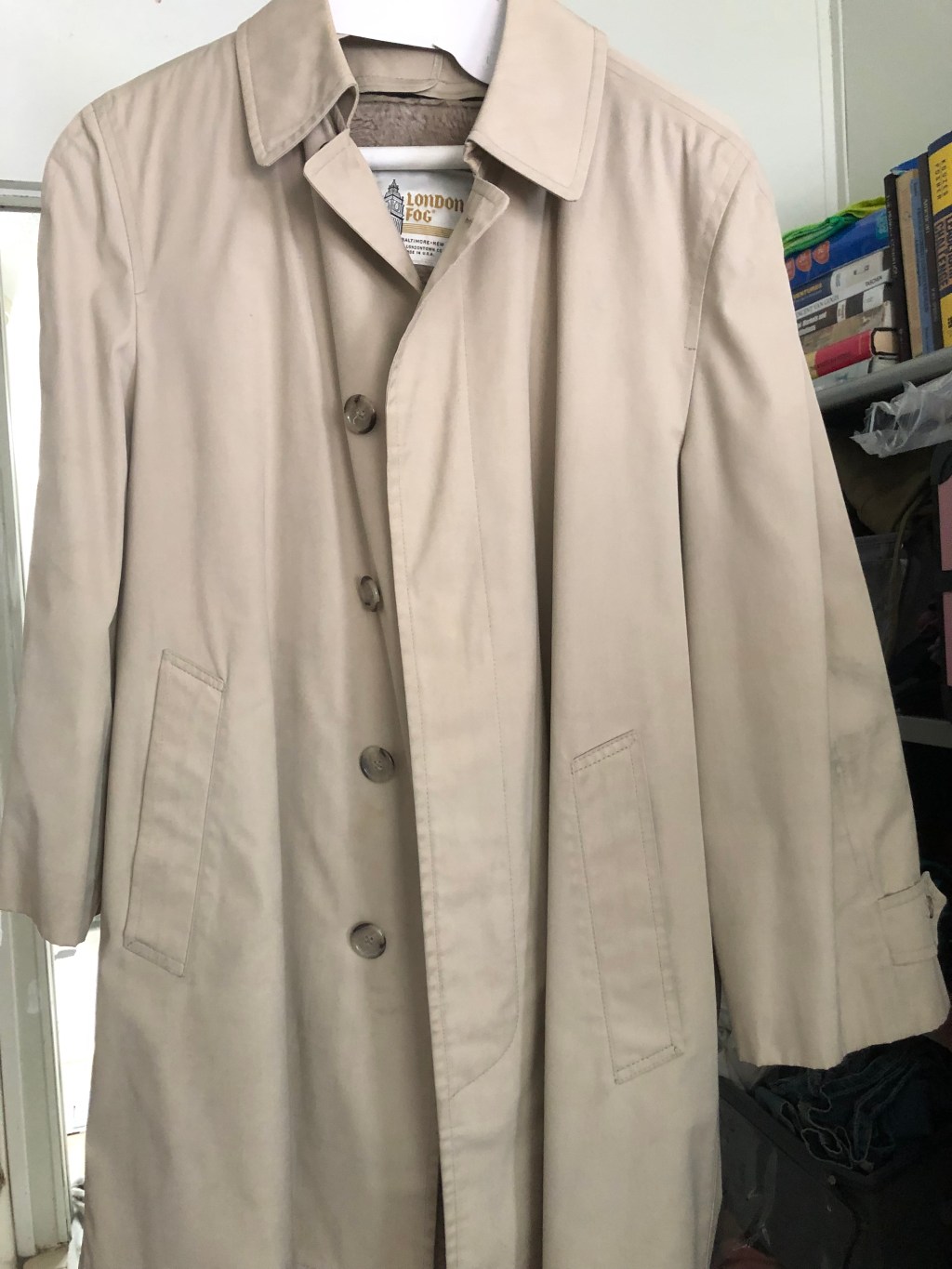

That trench coat is for visual aid – for my dad who once wore it in the cold of Northern Virginia. I cried at my first wedding when both of my parents were finally together at long last. It was an overdue catharsis: no country for young man, no Dad for young man, and no date for young man. “Christian” girls would politely accept dates only to brush off : “Don’t be a stranger” on weekdays as we rushed around to classes.

I learned not to grow attached and got my validation from social approval to the point of chronic abandonment. After all, the seed had long been sown, repeatedly each afternoon, when I was hungry yet plenty of song sheets to go before dad came home (we got to wait for family dinner).

Even then, often out of jealousy, our parents would food fight thus gone our long anticipated meals.

To clamp up and bottle up resentment, disgust and distastefulness for the thing called love came natural to me.

Yet through it all, decade-long gap included, I learned from my Dad to stand up to a bully, to tear up when it touches your soft core and to love music, language and to live life as it comes.

He was laid down on a cold gusty windy day. I would be without a coat but for his, for the duration of the service. Unconventional as it be ( wearing beige instead of black) at funeral, I was proud, perhaps never been prouder in my life, to be his son, his replacement in the world, where Child Welfare exists only for partial protection of abandoned and anchorless children. The rest is up to us, neighborhood watchers who like myself, once beaten bloody nose by bully, and experienced protection from and rescue by a loving and accepting father.

I am that prodigal son, but for that decade of separation, it wasn’t just me who were apart from my dad. From 1975 to 1985, it was a lost decade for all of Vietnam and its people. People left their home and one another. It’s shameful and even intentionally relegated into the recess of our memory. Just ask people on the Wall, out in the Sea and inside the Pentagon. Take my cousin as an example. She was an unacknowledged widow of war for almost five decades. My Dad and she used to go on gambling expedition together way back. I guess it’s the equivalent of their “deep-sea fishing”.

It’s eerie that my dad wore the same trench coat as McNamara’s Fog of War. Yet they couldn’t be further apart, since he was a victim of war, not an architect of it. Nor that we had ever gone deep-sea fishing together except for a drive around the beltway, during which I still remember him saying:

” Em nhu ru” (this ride is smooooooth).

Leave a comment